|

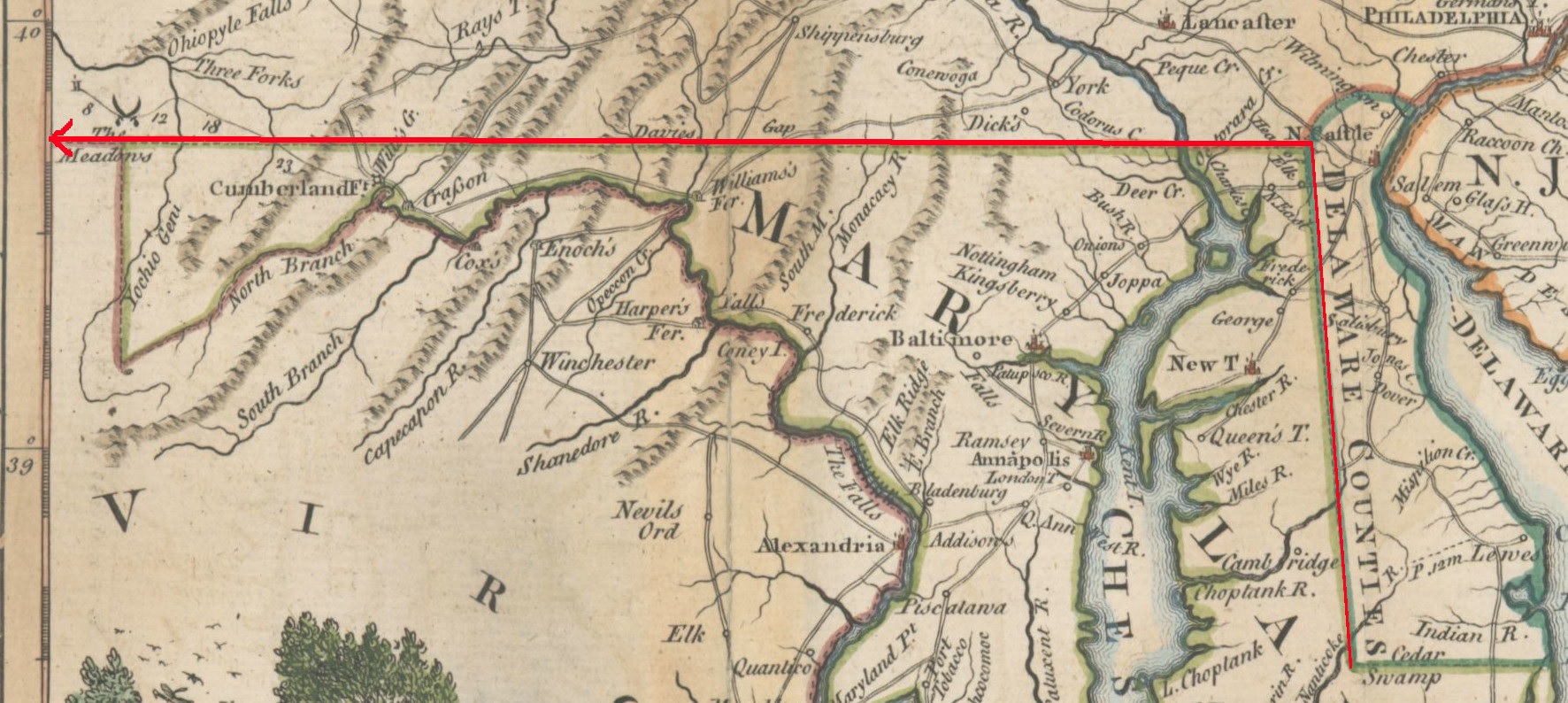

| The modern state boundaries surveyed by Mason and Dixon, in red. |

by Paul Lagassé

Maryland was granted to Cecil Calvert, the second Baron Baltimore, in 1632, and Pennsylvania was granted to William Penn in 1681. A year later, the Duke of York gave Penn a very-long-term lease (10,000 years) on what is now Delaware. Disputes over the boundaries between the Calvert and Penn lands began almost as soon as Pennsylvania was chartered. The quarrel outlived the original proprietors by decades, and a final, undisputed decision concerning the Calvert-Penn boundaries and how to mark them was not made until 1760.

Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, skilled in astronomy, mathematics, and surveying, were engaged by the Penns and Calverts to complete the work of marking the border between Pennsylvania and the Three Lower Counties (Delaware) and Maryland. The southern border of what is now Delaware had been marked along a Transpeninsular Line from the Atlantic to that line’s Middle Point, but local surveyors had difficulty surveying the next portion, the Tangent Line, which was to extend from the Transpeninsular Middle Point north to the Tangent Point with a 12-mile arc centered on the New Castle Court House. (The Delaware-Pennsylvania Arc boundary, first marked in 1701 and redrawn in 1892, enclosed lands Charles II granted to the Duke of York, lands later part of New Castle County. It was not surveyed by Mason and Dixon.)

The modern state boundaries surveyed by Mason and Dixon, in red.

Mason and Dixon were to survey the remaining unmarked sections of the border: the Tangent Line, the Arc Line (a small section of the 12-mile Arc that lies west of the North Line), the North Line (the border due north from the Tangent Point), and finally the West Line. The West Line was to run along a line of latitude located 15 miles south of Philadelphia’s southernmost point and extend 5 degrees of longitude west from the Delaware River, but the West Line The modern state boundaries surveyed by Mason and Dixon, in red. formed the border between Pennsylvania and Maryland only from its intersection with the North Line. Collectively these lines constitute the Mason-Dixon Line, and the survey that established it was one of the great technological feats of the 18th century, the product of painstaking astronomical observations and precise mathematical calculations, which sometimes required using spherical trigonometry.

The commissioners overseeing Mason and Dixon determined that the southernmost point in Philadelphia was the north wall of a house at what would now be 30 South Street (except that the location is under I-95). Going 15 miles due south from there would have forced the surveyors to cross the Delaware River as they surveyed south and then west. Instead, they would move some 31 miles west, to the farm of John Harlan, “in the Forks of the Brandywine” in Chester County. (His house survives at Stargazers and Embreeville roads outside Embreeville, Pa.) To start their survey there, they needed to know the southernmost point’s latitude, compare it with their latitude at Harlan’s farm, and then calculate the distance north or south between the two locations.

In Philadelphia, they established an observatory with state-of-the-art equipment that included a precision clock (chronometer) and the famous zenith sector telescope, and determined the latitude of the southernmost point. Then moving west and setting up their observatory next to Harlan’s house, they determined their new location’s latitude (about 0.2 miles south of the latitude of the house wall in Philadelphia). They also placed a “mark,” now known as the Stargazers Stone, several hundred feet north of their observatory on the same line of longitude that their observatory was on.

After completing this work in the spring of 1764, they measured, using survey chains and levels, some 14.8 miles south, to a location on a latitude 15 miles below the southernmost point, a spot now in Delaware’s White Clay Creek State Park. They determined its latitude and marked this reference point with the “Post mark’d West” (now memorialized by a stone monument). The surveyors were accompanied by a team of axemen who cleared a “visto” (a line of sight or vista) eight to nine yards wide along the line to be surveyed.

The survey team used the remaining months of 1764 to clear a visto for and survey the Tangent Line, beginning at the Transpeninsular Middle Point. Surveying an extremely straight reference line by using regular nighttime astronomical sightings to continually align their direction, they reached the area of the Tangent Point (82 miles north by north-northwest) and found the 12-mile marker post set earlier by local surveyors. They then used their new line; a second, check line they subsequently surveyed; and mathematical computations to determine the distances required to correct the Tangent Line surveyed earlier by local surveyors.

In 1765 Mason and Dixon began surveying the West Line from the Post mark’d West, reaching the Susquehanna River in May. The boundary between Maryland and Pennsylvania is a line of latitude, 39°43'18.2"N. That line, due to the earth's curvature, is not straight but gently curved, and cannot be surveyed easily. Instead, Mason and Dixon surveyed and temporarily marked an adjacent straight line (a great-circle segment) for 12 miles or so. After calculating the distances between the temporary mileposts on the straight line they had surveyed and the boundary's latitude, they then began the process again from their last marker, stopping at the Susquehanna. They subsequently moved the temporary mileposts to the calculated locations on the boundary.

Mason-Dixon Mile Marker 4, West Line, Big Elk Creek State Park

Returning east, they surveyed the North Line due north from the Tangent Point to its intersection with the West Line, a location now marked by the Tri-State Marker (on the southern boundary of Pennsylvania’s White Clay Creek Preserve; the original marker is lost). Because due north from the Tangent Point slices through the 12-mile Arc, a small section of the Delaware-Maryland border just north of the Tangent Point, known as the Arc Line, follows that Arc before the border runs due north. It was not surveyed, but was marked using calculations to determine its distance from the North Line. Mason and Dixon resumed surveying the West Line in mid-1765, now surveying two segments before calculating the offsets. They reached South Mountain and, in late October, North Mountain (Powell Mountain), where they halted for the year. They then began placing permanent stone boundary markers, work that they continued in late 1766 and finished as far as possible in late 1767.

In 1766 the survey extended the West Line to a point near the Eastern Continental Divide. The team also extended the West Line east from the Post mark’d West to the Delaware River, measuring that distance, without which they could not determine the 5 degrees of longitude that defined the western extent of Pennsylvania.

Local detail from Mason & Dixon's map.

Completing the survey of the West Line the full 5 degrees now depended on the cooperation of the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee, or Iroquois Confederacy), because King George III’s Proclamation of 1763 had restricted colonial settlement and travel west of the Eastern Continental Divide. After negotiations, the survey resumed in June 1767 from near Cumberland, Md., and now included a Mohawk and Onondaga escort party. In August, they passed the western end of Maryland’s border. Their subsequent surveying marked the Pennsylvania-Virginia (now West Virginia) boundary, which was disputed until 1779. In late 1767, after the Native American escort insisted that they go no farther because they had gone as far as the Six Nations had agreed they would go, surveying stopped not quite 233.25 miles from the Post mark’d West, some 19 miles short of the 5 degrees of longitude.

Mason and Dixon had proposed to the Royal Society that they measure a degree of longitude and, later, a degree of latitude. The Society did not fund the measurement of the degree of longitude, but it did fund their measurement in the first half of 1768 of a degree of latitude. That measurement was the first such to be made in North America, and the first anywhere by British scientists. They also calculated the length of a degree of longitude along the West Line. In August of 1768, Mason and Dixon delivered copies of a map of their boundary survey to the survey commissioners, and their work was completed. Eight years later, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Delaware became independent from the English king and from the proprietary governments of the Calverts and Penns.